In the mid-15th century, a remarkable depiction of the known world emerged from the workshop of a Venetian monk named Fra Mauro. Crafted around 1450, this monumental map, spanning over two meters in diameter, was meticulously drawn on parchment and mounted within a grand wooden frame.

Unlike most medieval maps, it positioned the south at the top, offering a fresh perspective on global geography. Today, this extraordinary artefact resides in Venice’s "Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana", where it continues to captivate scholars and visitors alike.

The Man Who Reimagined the World

Fra Mauro was a monk of the Camaldolese order from Murano, and was a visionary whose work bridged faith and reason. Though he lived within the quiet confines of monastic life, his intellectual reach extended far beyond the cloister walls. With a background in accounting, he possessed a keen eye for precision and a disciplined approach to information– qualities that would shape his groundbreaking map of the world.

Living in Venice, a bustling nexus of trade and exploration, he had access to a constant stream of knowledge. He gathered reports from merchants, sailors, and travellers, integrating their accounts with classical sources to construct a map that reflected the world as it was known, not as it was imagined through religious doctrine. His approach was empirical, favouring observation and experience over tradition.

Bridging Borders with Intellect

Commissioned by the maritime powers of Venice and Portugal, Fra Mauro’s map was used both as a navigational tool and as a philosophical statement. It rejected the symbolic centrality of Jerusalem and omitted any physical representation of Eden, marking a departure from the medieval Mappa Mundi. Instead, it embraced a secular worldview shaped by inquiry, exploration, and evidence.

The man's legacy lies in the intellectual shift he represented. He inked the dynamic curiosity of a world in motion. His work marked a turning point in cartography, laying the foundation for a more scientific and expansive understanding of the globe.

A Revolutionary Cartographic Achievement

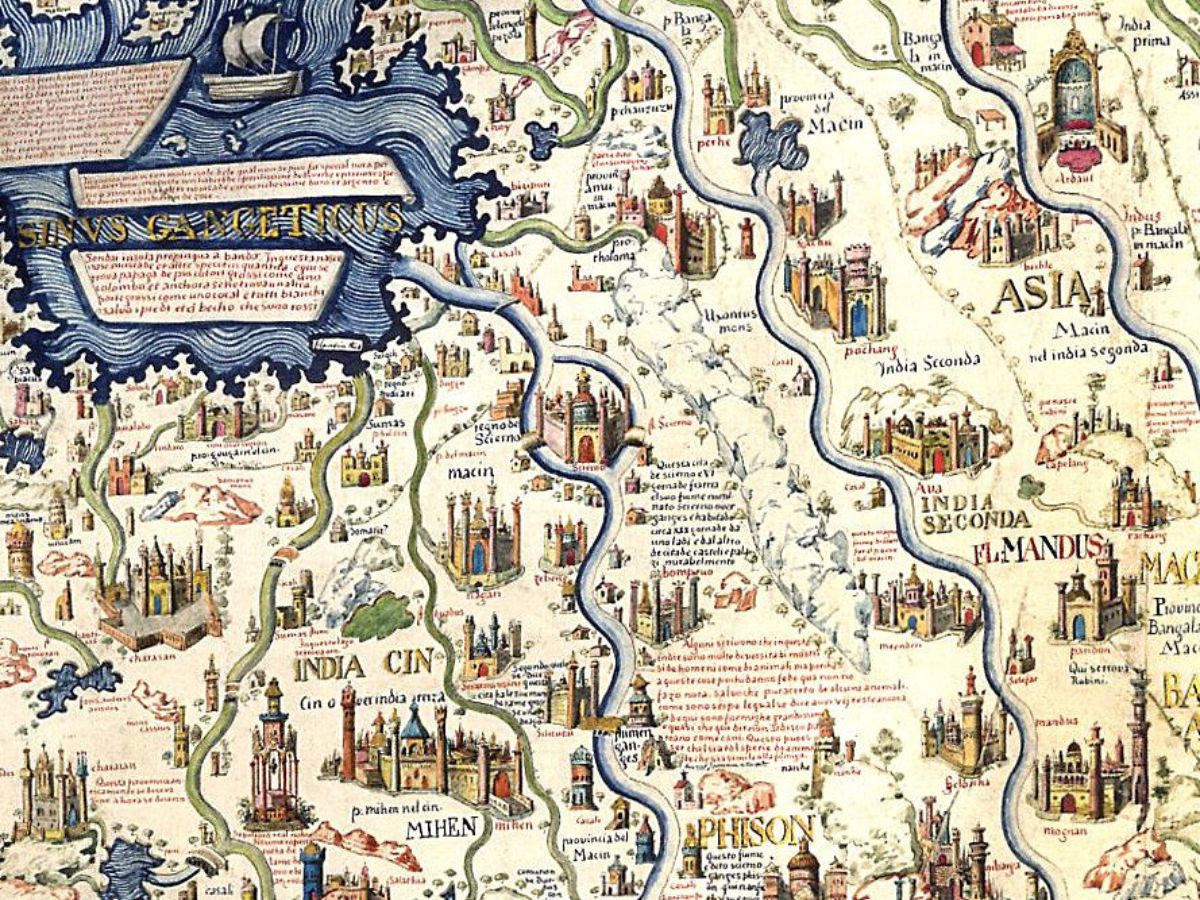

Fra Mauro's map stands as a remarkable accomplishment in the history of cartography, showcasing the intellectual ambition of its creator. One of the map's most compelling features is its extensive array of thousands of annotations and meticulously crafted illustrations.

These depict the geographical outlines of continents and oceans, outlining trade routes and providing curious insights. The map encompasses a diverse range of regions, extending from the vast landscapes of Asia and Africa to the distinct countries of Europe and the Atlantic Ocean.

This map represented a significant advancement in the field of mapmaking. Historian Jerry Brotton praises it as a pivotal moment in cartographic history, noting its significant departure from traditional religious symbolism, which had often dominated maps of previous centuries.

A Different Focus

Instead of centring on sacred locations, such as Jerusalem, the map embraces a more empirical approach, valuing observation and evidence over faith. This shift is particularly evident in its omission of Eden's physical location, marking a move towards secular mapping practices that prioritise factual representation of the world.

Through these innovations, Fra Mauro's map not only serves as a navigational tool but also reflects the changing perspectives of the time, emphasising a curiosity about and understanding of the world based on observation and exploration.

Diving Into the Map's Realm

The map measures an impressive 2.4 meters by 2.4 meters. This vast scale makes it the largest surviving map from early modern Europe. Crafted on fine vellum and enclosed in a gilded wooden frame, it's a fusion of artistic elegance and geographic understanding.

Its surface is adorned with dazzling pigments: shades of blue, red, turquoise, brown, green, and black were used to render intricate pictures with great precision.

At the centre lies a circular representation of the world, surrounded by four smaller spheres that expand its scope. One presents a Ptolemaic model of the cosmos, another illustrates the classical elements in sequence: earth, water, fire, and air.

A third offers a depiction of the Garden of Eden, which Fra Mauro notably places outside the terrestrial realm, challenging traditional cartographic conventions. The fourth sphere portrays Earth as a globe, complete with polar regions, the Equator, and the tropics.

Geography as a Trend

The map is densely annotated with approximately 3,000 inscriptions, each offering commentary on geographic features, cultural insights, and historical context. Its chorographic detail is exceptional, with mountains, rivers, and settlements depicted in a style that blends symbolic representation with visual storytelling.

Cities and fortresses are marked by stylised icons, their design reflecting their relative importance, making the tool as a trend of its time.

The creation of this map was a collaborative endeavour, led by Fra Mauro but executed by a team of skilled cartographers, artists, and scribes. The techniques employed were among the most sophisticated of the time, and the cost of production was equivalent to a year’s wages for a professional copyist.

Preservation Through Editions and Reproductions

The artist created two original editions of his world map. The first, commissioned by the Signoria of Venice, was rediscovered at the Monastery of St. Michael in Murano and is now displayed at the Museo Correr in Venice.

The second, made for King Afonso V of Portugal– with help from Andrea Bianco, was completed in 1459 and sent to Lisbon. It was kept at São Jorge Castle until at least 1494, and a 15th-century version is now on display at Lisbon’s naval museum.

In 1804, British cartographer William Frazer produced a faithful vellum reproduction, now housed in the British Library.

The map has been studied by historians since 1806, with a critical edition published by Piero Falchetta in 2006.

Orientation and Centre

Fra Mauro’s map is unmistakably distinctive for its unusual orientation, with South positioned at the top. Though this might seem confusing to us, it aligned perfectly with Arab mapping conventions and the south-pointing compasses used during that era.

Unlike the east-facing European maps, or the north-oriented Ptolemaic maps, his plan was guided by practical and empirical concerns. He openly accepted Ptolemy’s influence, but still argued that strict adherence to ancient geography would have excluded many newly known regions:

“To follow Ptolemy’s coordinates would mean omitting vast areas unknown in his era, especially in the southern latitudes.”

Western Europe

The section of the map depicting Europe, particularly the regions near Fra Mauro’s native Venice, demonstrates the highest level of cartographic precision. It includes detailed renderings of the Mediterranean basin, the Atlantic shoreline, the Black Sea, and the Baltic region, reaching as far north as Iceland.

Coastal outlines are remarkably accurate, with all significant islands and landforms clearly marked. Numerous cities, rivers, and mountain ranges are also represented, reflecting a deep familiarity with the geography of the continent.

The British Isles

The map features two explanatory notes concerning England and Scotland, blending mythological and historical narratives. One legend recounts that England was once inhabited by giants, until survivors from the fall of Troy arrived, led by Brutus, and claimed the land.

The territory was subsequently named "Britannia" in his honour. Later, Saxons and Germans took control, renaming it "Anglia" after Queen Angela. The conversion of these peoples to Christianity is attributed to Pope Gregory, who dispatched Bishop Augustine to evangelise the region. This tale echoes themes from the 12th-century chronicle "Historia Regum Britanniae", which popularised the legend of King Arthur and traced Britain's origins to Trojan lineage.

Scotland is portrayed as adjoining England, though separated in the south by natural barriers of water and mountains. The residents are described as peaceful, yet fiercely independent– preferring death to subjugation. The land is noted for its abundance of pastures, rivers, springs, and wildlife, bearing similarities to England in its fertility.

Northern Europe

The portrayal of Scandinavia may lack the precision found in other regions, but a captivating legend paints Norway and Sweden as realms occupied by towering, mighty people. Their presence looms large, embodying the rugged spirit of the north and the enchanting landscapes that surround them.

Norway in particular is portrayed as a vast coastal province connected to Sweden, lacking in wine and oil production. The people are characterised by their strength and imposing stature.

Sweden’s warriors are said to have intimidated even Julius Caesar, and during Alexander the Great’s era, the Greeks reportedly avoided conflict with them. Though once a formidable force, these populations are now considered diminished.

Picturing the East

The Asian portion of the map includes the Arabian Peninsula, Persia, the Indian subcontinent (with Sri Lanka), the islands of Java and Sumatra, Burma, China, and Korea.

The Caspian Sea is accurately shaped, but the southern regions of Asia are misrepresented, with India shown as two separate landmasses. Prominent rivers such as the Tigris, Indus, Ganges, Yellow River, and Yangtze are illustrated.

Fra Mauro’s map is also one of the earliest European cartographic works to depict Japan, possibly influenced by the De Virga map. The piece shows a part of Japan, likely the island of Kyūshū, positioned below Java and labelled as "Isola de Cimpagu." This is a misspelling of "Cipangu," the name Marco Polo used to refer to Japan.

The African Continent

The southern tip of Africa, features islands with names rooted in Arabian and Indian languages, such as Nebila, meaning “celebration” or “beautiful” in Arabic, and Mangla, indicating “fortunate” in Sanskrit.

These lands are often associated with the legendary “Islands of Men and Women,” a myth recounted by Marco Polo.

According to this tale, one island was inhabited solely by men, and the other by women, who met only once a year for procreation.

While Fra Mauro placed them near the Cape of Diab, Marco Polo suggested they were close to Socotra, and other medieval cartographers speculated locations in Southeast Asia, such as near Singapore or the Philippines.

The Indian Ocean

The Indian Ocean is represented as open and connected to the Pacific, a significant departure from earlier conceptions of a closed sea.

It includes detailed reports of island groups such as the Andamans and the Maldives.

Near the southern tip of Africa, tagged “Cape of Diab,” Fra Mauro inscribed a narrative of a voyage undertaken around 1420. A large Indian ship, referred to as a “junk” or “Zonchi,” sailed southwest from India toward the Islands of Men and Women. After 40 days at sea, encountering only wind and water, the ship had travelled approximately 2,000 miles before turning back, taking 70 days to return.

Fra Mauro believed that Africa could be circumnavigated, a conviction strengthened by various narratives and ancient references. For instance, Strabo described Eudoxus of Cyzicus sailing from Arabia to Gibraltar. This insight, along with the way Africa was depicted on the map, likely influenced the Portuguese attempts to sail around the continent's tip.

The American Limit

In 1450, the extent of European knowledge regarding the Americas was quite minimal, with the only known land being Greenland, which appeared on contemporary maps labelled as “Grolanda.”

During this time, the artist adopted the novel idea of a spherical Earth. However, in his pictures, he represented the Earth as a disc encircled by water rather than a true sphere.

He made significant estimations concerning the Earth's size, calculating its circumference to be between 22,500 and 24,000 miles. These figures were surprisingly close to modern measurements, reflecting the advanced understanding of geometry and geography that was beginning to emerge during this period of exploration and discovery.

Sources & Origins

The map’s sources included existing charts, manuscripts, and extensive traveller accounts. Niccolò de’ Conti’s 20-year journey through Asia contributed significantly, as did Marco Polo’s writings.

For African geography, Fra Mauro drew on Portuguese exploration and possibly information from an Ethiopian delegation to Rome. Arab cartographic traditions also influenced the map, evident in its south-oriented layout. Oral testimonies from travellers arriving in Venice played a crucial role, making his piece a unique blend of myth, observation, and global knowledge.

A Timeless Influence

The Fra Mauro map reflects the intellectual curiosity and global awareness of 15th-century Venice. Far more than a navigational tool, it encapsulates a worldview shaped by trade, exploration, and cultural exchange.

Its detailed depiction of continents and legends reveals a sophisticated understanding of topography that challenged conventional beliefs and anticipated future discoveries. As both a scientific and artistic masterwork, the map continues to inspire historians, geographers, and explorers alike, reminding us that the pursuit of knowledge is a journey without borders.

.avif)