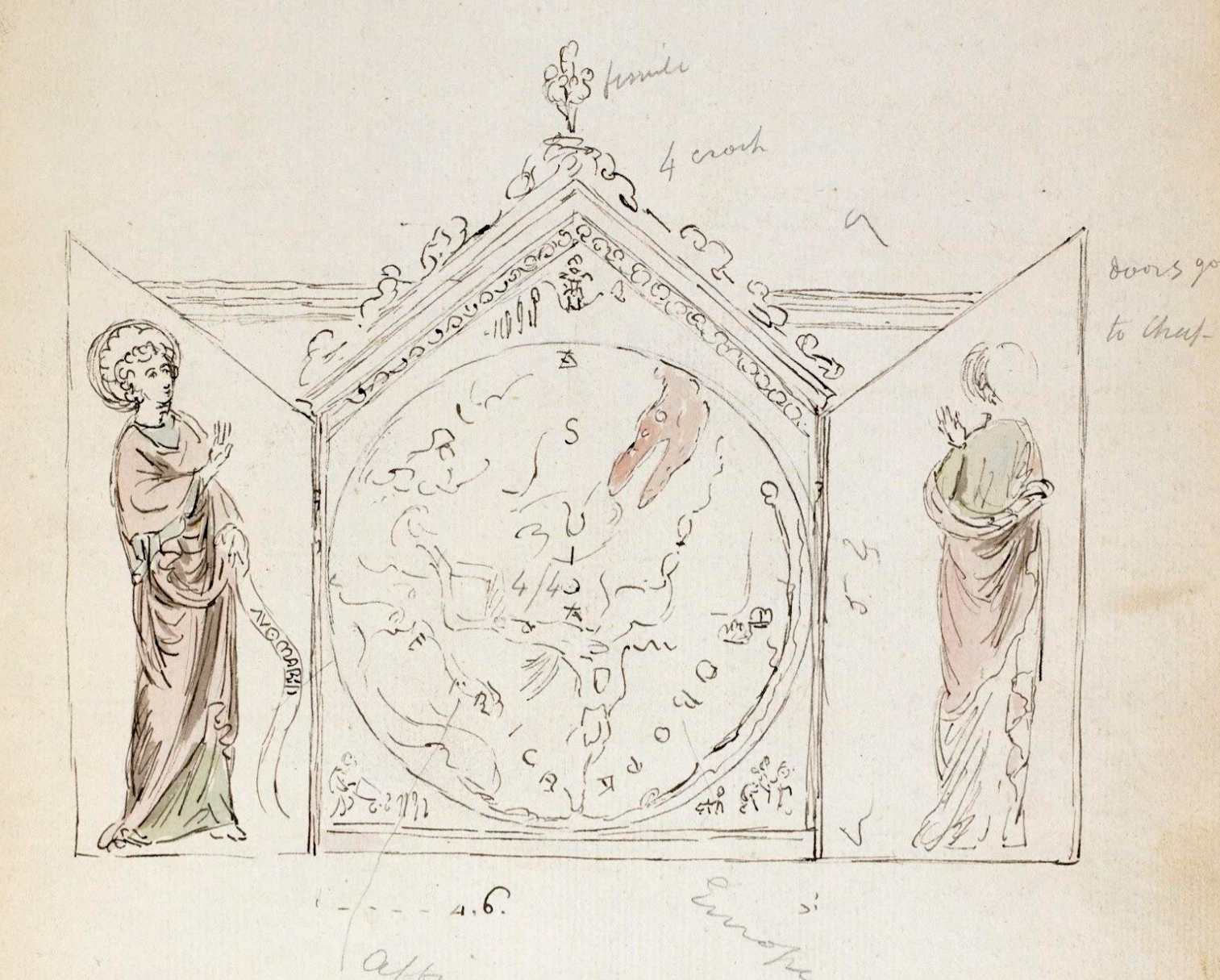

During the Middle Ages, creating world maps was a unique speciality in England. These were often drawn on materials such as cloth, walls, or animal skin. The Hereford World Map, also known as the "Mappa Mundi", is the only complete map from that era that managed to survive, and is considered the largest medieval map in existence.

These kind of maps were intricately detailed, but could only be understood by those who spoke Norman French, the language of the literate secular elite. The Mappa Mundi, not only depicted geographical features, but also interpreted the world in spiritual terms. This included Biblical illustrations, alongside representations of Classical learning and legends.

As visual descriptions of the world, these impressive guides served an educational purpose; they were used to teach natural history, legends, and to reinforce religious beliefs.

Hereford Cathedral, located near the Welsh border on the River Wye, has been a site of worship since the end of the 7th century. The current structure was rebuilt in the 1100s and is regarded as one of the finest examples of Norman cathedral architecture in the UK.

What makes this place truly unique is its ability to preserve many ancient treasures over the centuries. It houses the largest surviving chained library in the world and one of the only remaining copies of the 1217 Magna Carta.

Mappa Mundi - Design and Precision

The Mappa Mundi stands as one of the most extraordinary treasures of the medieval world, a captivating tapestry of human understanding from a bygone era.

It measures a striking 1.59 x 1.34 meters (5 feet, 2 inches x 4 feet, 4 inches), and it's crafted from a singular, fine sheet of vellum, derived from calfskin.

Scholars speculate it was created around the year 1300, capturing history, geography, and the human narrative as perceived through the lens of Christian Europe during the late 13th and early 14th centuries.

Signed by Richard of Haldingham and Lafford, known in the annals of history as "Richard de Bello", the map showcases lavish lettering rendered in elegant black ink, accentuated with rich splashes of red and gleaming gold. The seas and rivers shimmer in hues of blue and green, with the Red Sea boldly painted in a vivid crimson.

Within its elaborate design, the map depicts an astounding 420 cities, 15 pivotal biblical events, 33 species of flora and fauna, 32 notable figures, and five enchanting scenes drawn from classical mythology.

At its heart lies Jerusalem, illustrated as the focal point of this grand representation. Uniquely, the map is oriented with east positioned in the upper left, a curious twist of tradition that flips the cardinal directions: west now faces south.

This is evidenced by traces of a dark background paint, altered to introduce bold black

characters that replace the original light inscriptions of Africa and Europe, resulting in a

playful yet confusing reversal of their names. Europe is whimsically rendered in red and gold as "Africa," while Africa bears the opposite designation.

The Hereford Mappa Mundi bears significant similarities to the Ebstorf Map, the Psalter World Map, and the Sawley Map, previously misidentified as the "Henry of Mainz Map".

The Caspian Sea is whimsically illustrated as an arm of the ocean that encircles the world, ignoring the clear reports from William of Rubruck in 1255 that it was surrounded by land.

The map delineates continents through the fluid lines of the Mediterranean Sea and the meandering courses of the Don and Nile rivers. In a groundbreaking first, it even mentions the elusive Faroe Islands, adding to its multifaceted record and making the Hereford Mappa Mundi an invaluable glimpse into medieval knowledge.

Through History and Time

The Hereford Map has been displayed on a corridor wall at Hereford Cathedral for many years. During the Interregnum period, it was concealed beneath the floor of Bishop Audley's votive altar, where it remained hidden for a significant duration. In 1855, the map was restored and subsequently transferred to the British Museum. During World War II, it was safeguarded and returned to Hereford in 1946.

In 1988, in response to a financial crisis within the Diocese of Hereford, there was a proposal to sell the map. This sparked considerable public controversy, but thanks to the generous contributions from the "National Heritage Memorial Fund", Paul Getty, and numerous visitors, the Hereford Map was ultimately preserved. A new library was built to house the map, which was officially inaugurated in 1996. Today, the Mappa Mundi continues to be preserved and is displayed in Hereford Cathedral, England.

In January 2013, Factum Arte was commissioned by the Mappa Mundi Trust to conduct the first high-resolution 3D scan of the map. The fragile surface of the Hereford Mappa Mundi, which has a sealed glass cover (only removed once every two years for inspection and maintenance), was recorded using Factum's Lucida 3D Scanner to capture detailed information about its shape and texture.

Six months later, a plaster cast of the Mappa Mundi was presented to Hereford Cathedral. A custom display crate was specially designed and fabricated from cherry wood. This display consisted of two parts that could function both as a transport box and as a presentation for the plaster cast, with the surface oriented horizontally. A LED strip was also incorporated at the top to provide raking light on the surface, highlighting the relief of the map.

In January 2016, three years after the initial 3D recording of the Mappa Mundi, a team from Factum Arte, returned to Hereford Cathedral to complete the second phase of this unique documentation project. This involved recording the colours of the map and scanning the surface of the wooden backboard on which the map may have originally been drawn. Even today, the map is carefully observed and maintained.

The Mappa Mundi, was crafted not merely as a navigational tool but as a profound

representation of the world through a spiritual and human lens. Its artistry reveals a blend of incredible precision but silly misinterpretations, capturing the imagination of its spectators. Europe and Asia are boldly portrayed, albeit with their labels intriguingly reversed, while a captivating array of mythical beasts and scenes drawn from Biblical narratives leap from the parchment.

Vivid imagery of tribes and classical myths intertwine with carefully delineated water sources. The Red Sea flows in a striking, rich ink, oceans are rendered in serene green, and rivers curve in deep blue.

Where the Complexity Lies

This magnificent map, as already mentioned, boasts great illustrations, featuring cities and towns, spiritual episodes, scenes from mythology, and a rich assortment of 32 human figures. Each representation is adorned with a caption, masterfully inscribed in Latin, inviting exploration into the stories of distant lands.

Among the illustrations, notable places such as Jerusalem and Babylon stand out, along with the small village of Hereford itself.

It reflects the artistic conventions of its era, reminiscent of other renowned cartographic works. Yet, the Mappa Mundi captivates students and enthusiasts alike with its enchanting allusions, whimsical illusions, and exquisitely rendered labels, crafting a visual narrative that beckons viewers to lose themselves in its depth and detail.

Meaning ‘atlas’ or ‘sheet of the world’ in Latin, the map is listed on Unesco's Memory of the World Register and is described as "the only complete example of a large medieval world map intended for public display". In many ways, it functions as a visual encyclopedia from the period.

Emerging theories about the Hereford map are continuously reshaping our understanding of this historical artefact, igniting lively debates among students and historians.

One notable argument set by Kupfer, describes the map as encapsulating two contrasting perspectives of the world: The first, offers a humanistic and temporal view, emphasising the lived experiences, environments, and cultures of humanity.

The second perspective reflects a divine worldview, illustrating how the universe is perceived through a spiritual or celestial lens, underscoring themes of divinity and the cosmos.

This duality in interpretation invites a deeper exploration of how medieval societies

understood their place in the world, both on earth and in relation to the heavens.

For centuries, it was believed that the calligrapher of the map had mistakenly labelled the

continents of Asia and Europe. However, Kupfer suggests that this may have been an

intentional "artistic invention" and one of several examples of mirrored imagery within the map itself.

Another theory, proposed by Firman, argues that the cities, people, and animals depicted within the circular boundary of the map, represent earthly concerns constrained by time.

In contrast, certain Biblical scenes placed outside the Earth's circle– such as Christ’s Last Judgment, are depicted as timeless.

The charm of this outstanding Mappa Mundi lies deeply embedded in enigmas, with each detail telling a story of its own.

With deep colours and meticulously illustrated features, it draws the attention of historians, adventurers, and inquisitive minds from around the world.

Ancient landmarks are rendered with precision, inviting viewers to delve into the past. This mesmerising portrayal not only sparks a profound sense of wonder, but also beckons exploration, lighting an insatiable curiosity that enriches both the intellect and the spirit, encouraging a search for knowledge and discovery that transcends borders.

.avif)