In the second century CE, the renowned Greco-Roman scholar Claudius Ptolemy conducted his research in the bustling and culturally rich city of Alexandria, producing two groundbreaking works that would leave a lasting mark on the world's academic landscape.

The Almagest

The first was the Almagest, a comprehensive astronomical treatise that established the geocentric study of the universe. Ptolemy placed Earth firmly at the centre of the universe and described the movements of the Sun, Moon, and planets using systems of deferents and epicycles.

By blending observation with mathematical design, he created a model convincing enough to guide astronomical thinking for more than a thousand years.

The Geographia

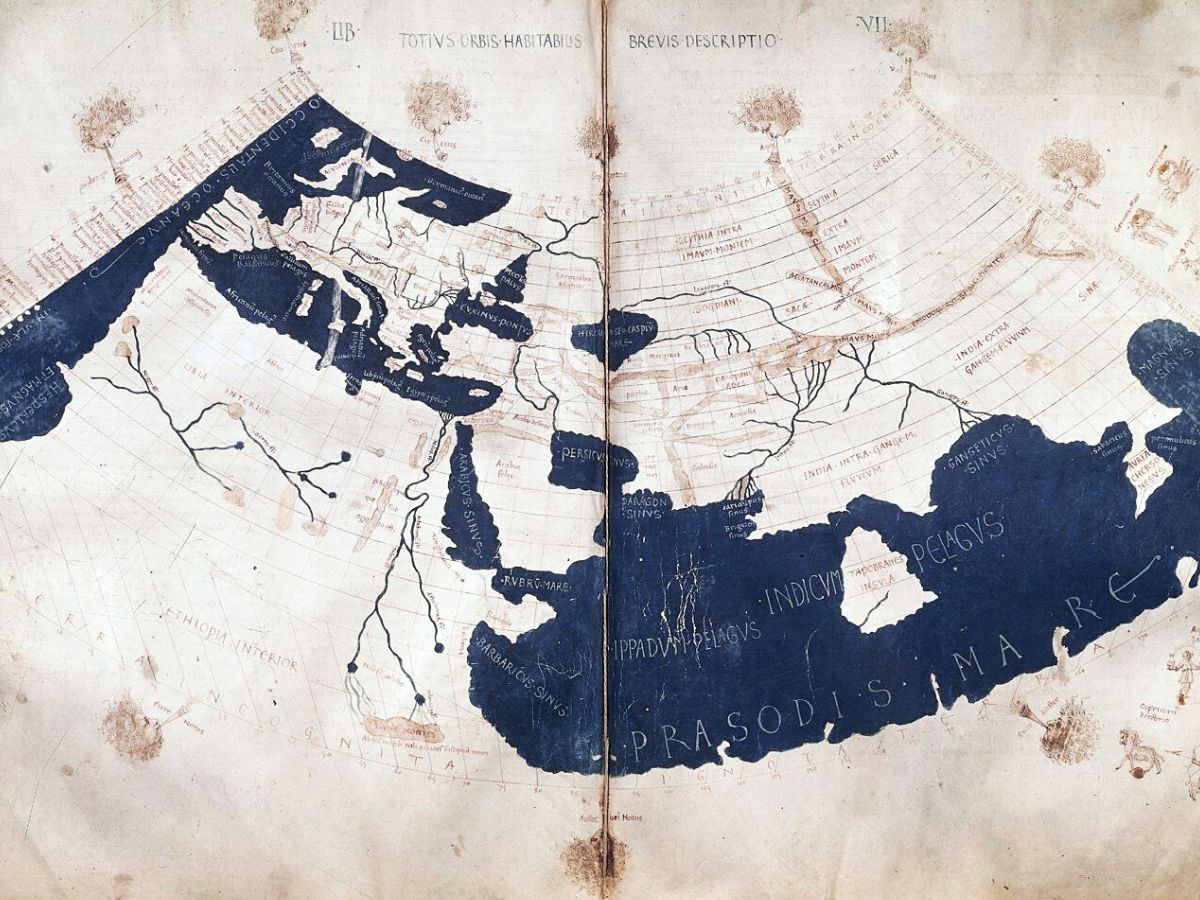

The second was the Geographia, a treatise on cartography that introduced a systematic method for mapping the known world using coordinates of latitude and longitude. Together, these works mapped both the heavens and the Earth, embedding the author's worldview into the foundations of science, philosophy, and geography.

His studies shaped the scientific understanding of his time and set the stage for future advancements in these fields for centuries to come. Ptolemy's meticulous observations and methods contributed to a body of knowledge that would influence scholars, astronomers, and explorers long after his lifetime.

Philosophical Meaning of the Geocentric Model

Ptolemy’s geocentric worldview transcended mere scientific hypothesis; it was a profound philosophical message. By placing Earth at the centre of the cosmos, he supported the dominant ideas of order, hierarchy, and stability in society.

This model not only aligned with the traditions that valued symmetry and balance, but also echoed the prevailing religious and philosophical beliefs regarding humanity's key role in creation.

For over a thousand years, this concept reigned supreme in every field, shaping the thoughts of scholars from late antiquity through the Middle Ages, until Copernicus started questioning it in the sixteenth century.

.jpg)

Geographia's Impact

The Geographia was equally transformative. Ptolemy introduced the idea of representing locations mathematically, assigning coordinates to more than 8,000 places across the world.

This innovation turned geography from a descriptive narrative into a discipline grounded in calculation. His use of latitude and longitude created a grid system that allowed future generations to reconstruct maps, even when the original manuscripts were lost.

He also experimented with projection methods, attempting to translate the curved surface of the Earth onto a flat map. Though his results were unsatisfactory, they designated a crucial step toward modern cartographic science.

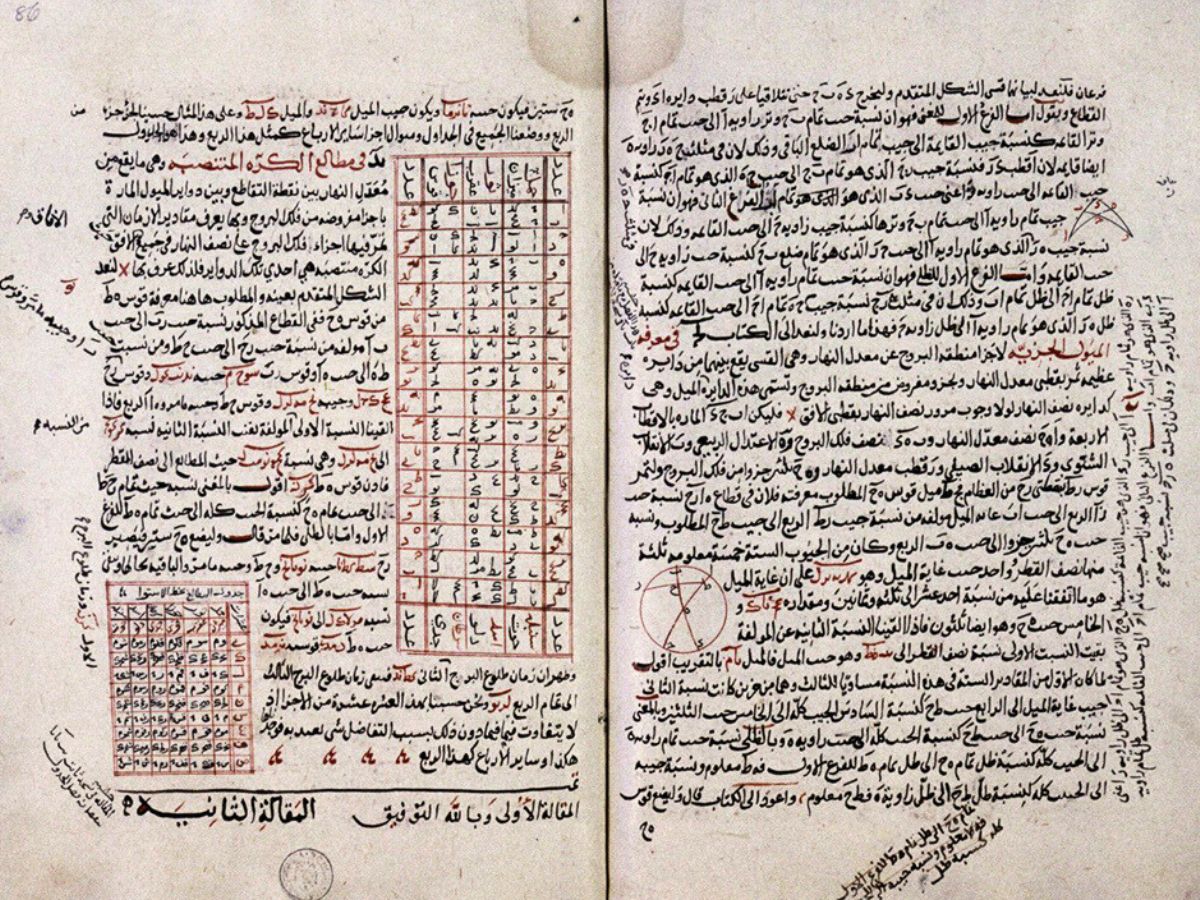

Transmission Through Islamic Scholarship

Ptolemy's work extended beyond the confines of Alexandria, significantly influencing various cultures. In the ninth century, Islamic scholars translated his Geographia into Arabic, thereby incorporating it into the resounding tradition of Islamic cartography.

Notable figures such as al-Khwarizmi built upon the astronomer's methods, merging them with insights from Persian and Indian sources. These translations played a vital role in preserving his legacy, ensuring that his ideas would resurface in Europe during the Renaissance.

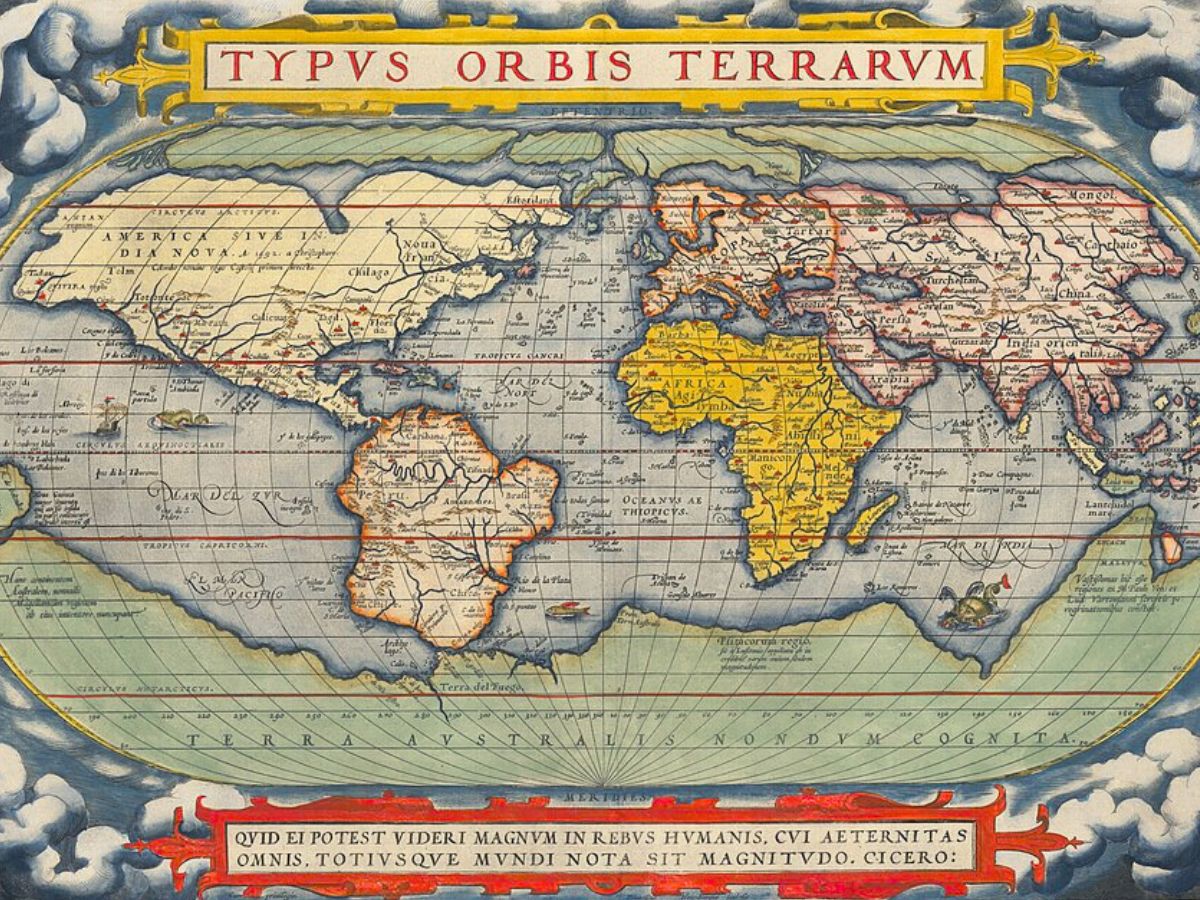

Renaissance Rediscovery

In fifteenth-century Italy, the rediscovery and printing of the Geographia sparked a cartographic revolution. Humanists and mapmakers used Ptolemy’s coordinate system to reconstruct maps of the ancient world, and his methods influenced figures such as Leon Battista Alberti and Gerardus Mercator.

During the Age of Exploration, navigators such as Christopher Columbus relied heavily on Ptolemaic maps to guide their journeys across the Atlantic.

While these maps were based on Ptolemy's calculations, which underestimated the Earth's circumference and distorted the shapes of continents, they nonetheless offered a structured framework that explorers used to navigate and chart new routes. Despite their inaccuracies, these maps marked the advancement of exploration during this period.

Scientific Methods and Flaws

Ptolemy’s cartographic system stands out for its impressive scientific rigour and reproducibility, marking a significant advancement in the field of geography. By introducing a structured coordinate system, he created a versatile technique that enabled scholars of his time to meticulously plot and compare locations with remarkable precision.

This innovative approach allowed for a more systematic study of topography, fostering a deeper understanding of spatial relationships across various regions.

Ptolemy’s reflections collected various traditions into a unified and coherent system, which laid down the foundational principles of cartography that would endure for centuries. His maps depicted a complex interplay of observation and calculation.

However, his project was left with flaws. Ptolemy's maps often misrepresented the actual dimensions and shapes of continents, particularly Africa and Asia, where landmasses were frequently truncated or distorted. His estimates of the Earth's size were inaccurate because, at that time, there was no reliable method for determining longitude.

Additionally, his use of a smaller Earth circumference contributed to even more errors, resulting in significant distortions, such as Greenland appearing larger than Africa.

Furthermore, his representations entirely omitted the Americas, reflecting the geographical knowledge available during his time. These inaccuracies certainly serve as a reminder of the constraints of ancient knowledge, yet they don't overshadow the profound and lasting influence that Ptolemy's methodologies had on the evolution of cartography.

Legacy in Science and Cartography

The mathematician's map acts as a significant artefact, representing a mental composition that integrates mathematics and cosmology to understand the world. His perspective influenced not only the field of astronomy, but also shaped societal perceptions of humanity's place in the universe.

The coordinate-based mapping system he developed laid the groundwork for contemporary geographic information systems (GIS), where coordinates are fundamental to spatial analysis.

Although his cosmological theories have been revised, his practices continue to inspire and inform. Renaissance cartographers enhanced his projections, and the foundational principles he established remain integral to modern scientific tests.

Enduring Vision

The heritage of Ptolemy’s work lies in its ability to bridge science, philosophy, and culture. He created a map of the world, and of human vision, charting the intersection of calculation and purpose.

By placing Earth at the centre of the universe and embedding geography within a grid of numbers, he created a sight that guided explorers and inspired scholars. His results remind us that even flawed visions can illuminate pathways to discovery, and that the act of mapping is as much about understanding ourselves as it is about charting the world.

For those interested in my own work, the path to follow is considerably easier.

Consult my blog or social media profile, where I share my daily craft and give updates on my projects.

Needless to say, I often talk about globe-making lore in depth, as a way to spread knowledge and appreciation for this beautiful craft.

.avif)