Within the political and symbolic residence of the Medici dynasty, known as the Palazzo Vecchio in Florence, Cosimo I de' Medici created a space that functioned not just as a storage room, but as a true centre for intelligence and the representation of knowledge.

The Sala del Guardaroba, also referred to as the "Sala delle Carte Geografiche" (Hall of Geographic Maps), stood as a unique place in the sixteenth century. It served as a venue where the collection of documents, treasures, and objects was intertwined with the ambition to catalogue and visualise the entire known world.

A cosmographic theatre of power and knowledge

This was a laboratory of power and knowledge, a cosmographic theatre that reflected the duke’s will to dominate reality through its representation. The project, with its encyclopedic approach, aimed to transform the governance of the city into an exercise in informed control, in which the geography of power manifested itself in the control of the geography of the world.

The ordered system of drawers

The hall was equipped with hundreds of drawers, methodically arranged and organised, designed to contain an impressive variety of materials. There were administrative and diplomatic documents, precious treasures gathered from missions and embassies, natural specimens from distant lands, scientific instruments, and objects of symbolic value.

Classification and accessibility of knowledge

Each drawer fitted into a coherent classification system, designed to make accessible and organised a worldly and intellectual patrimony.

Cosimo I imagined the lobby as a universal archive, a repository serving both the practical management of the State and the construction of an image of cultural and political dominance.

The hall’s use for confidential consultations, diplomatic exchanges, strategic planning, and scenographic presentations to high-ranking visitors gave this space a double identity: workshop of power and chamber of marvels.

Cataloguing and visualising the world

The true innovation of the Sala del Guardaroba lay in its conception as a space of global cataloguing. It was about making the order of the world visible and understandable to everyone.

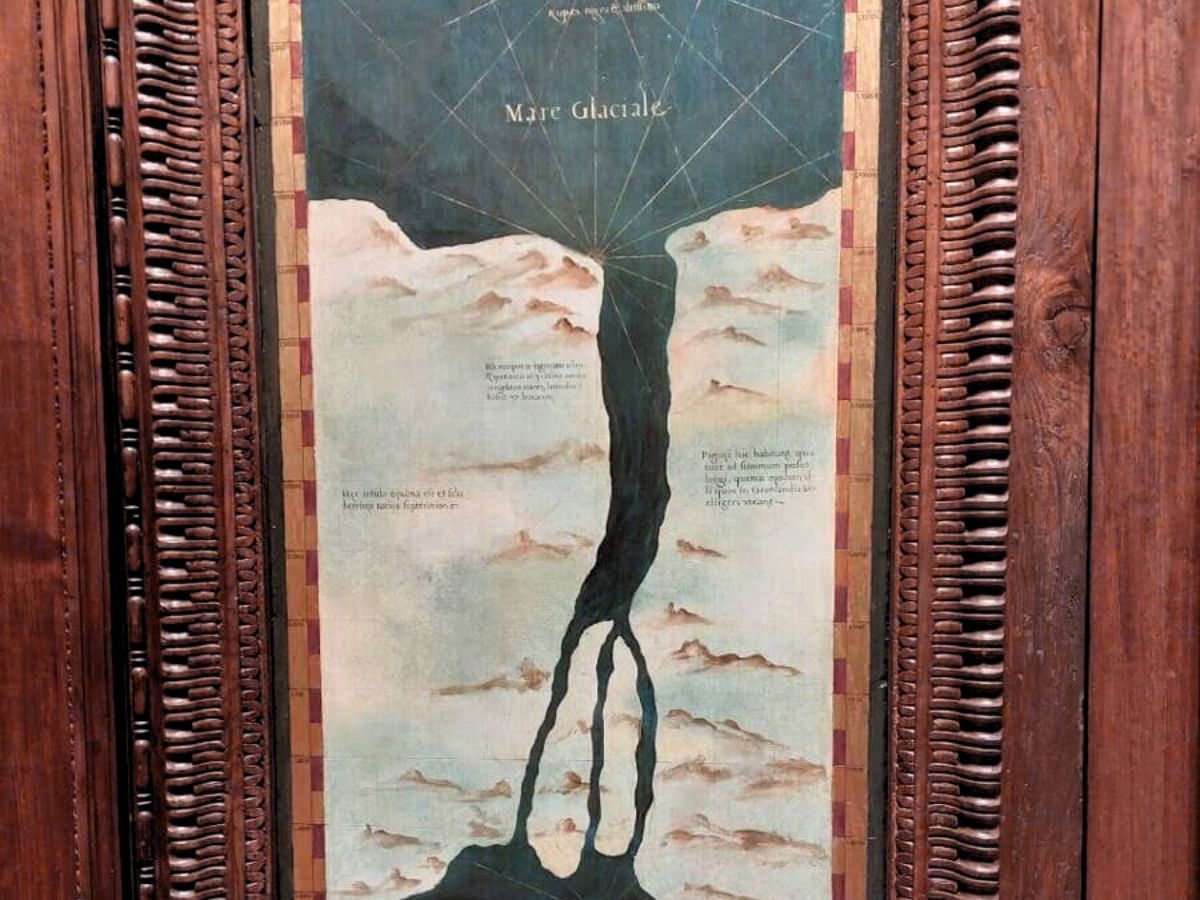

The cabinet doors were decorated with large, carefully painted maps that transformed the area into a visual inventory of known territories. Each cabinet corresponded to a region, a continent, a fragment of the globe, creating a mosaic that allowed viewers to embrace the totality of the earth at a glance.

Maps as a visual inventory of global territories

The project was undoubtedly ambitious, showcasing the Renaissance ideal of universal knowledge and the Medici's intent to position themselves at its centre.

The maps painted on the cabinet doors formed the visual heart of the hall. Each panel depicted territories with geographic details, descriptive cartouches, information on boundaries, cities, rivers, and reliefs, sometimes accompanied by notes on peoples, resources, and products.

A three-dimensional atlas and the language of power

In this way, the hall became a three-dimensional atlas, a place where the visitor could traverse the globe through coordinated images. The maps were conceived as a visual inventory, a way to symbolically possess the world through its representation.

Geography became a language of power, and the hall itself a manifesto of the Medici capacity to dominate space and knowledge. The accuracy of some regions and the exoticism of others coexisted in a synthesis that illuminated both the ambition for truths and the web of diplomatic relations at the Florentine court.

Ignazio Danti and astronomical knowledge

The realisation of the maps was fundamentally based on the work of Ignazio Danti, the cosmographer and mathematician commissioned by Cosimo I. Danti utilised his expertise in astronomy and cartography to transform the sixteenth-century concept of the world into visual representations.

Between 1563 and 1575, he painted a significant portion of the planned maps. His work followed an order inspired by the Ptolemaic tradition while also incorporating new geographic discoveries that emerged from oceanic voyages.

References and scientific rigour

His work didn't limit itself to the representation of lands; it also included the use of astronomical references to determine latitudes, orientations, and proportions, and the idea of a large terrestrial globe as a complement to the wall maps.

Danti united scientific rigour and artistic sensitivity, creating an ensemble that reflected both mathematical precision and the will to astonish and impress.

The presence of latitude values, the care for meridians and parallels, and attention to the orientation of coasts attest to the attempt to combine celestial observation and terrestrial description, reflecting cosmography as a bridging discipline between sky and earth.

Perimeter cabinets and stations of observation

The Sala del Guardaroba was designed with a combination of furniture, maps, and ceiling decorations that together created a cohesive and evocative environment. Monumental wooden cabinets with painted doors lined the perimeter of the room, organising the space into designated areas for consultation and observation.

Cosmic motifs and an ordered microcosm

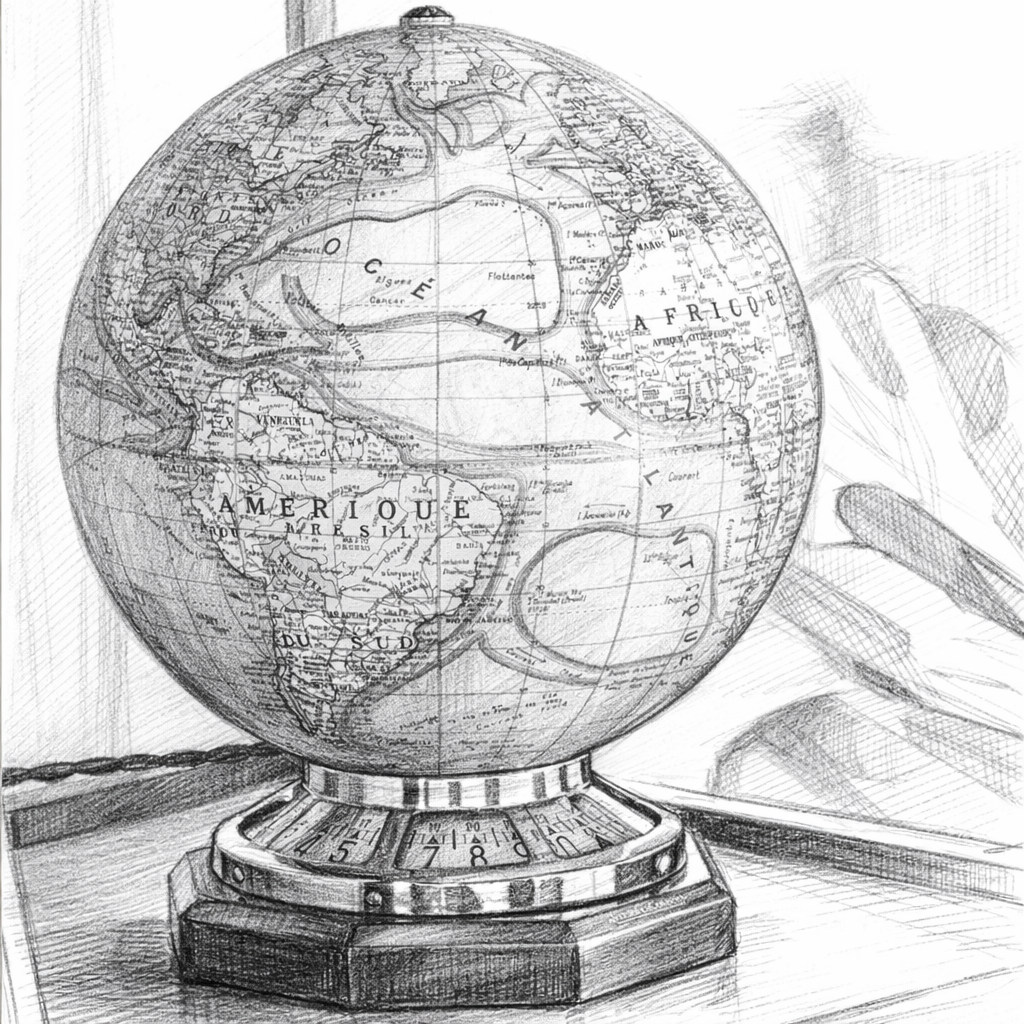

The ceiling was adorned with motifs recalling cosmic, astrological, and allegorical themes, completing the idea of an ordered microcosm. At the centre, the large terrestrial globe enhanced the understanding of the world and served as a focal point, encouraging circulation and comparison between flat and spherical perspectives.

The overall effect was that of a performance, where every element contributed to constructing an image of universal order. The hall wasn't only functional but also scenographic: designed to impress, engage, and communicate a message of power and modernity.

Cartographic details and sixteenth-century geography

The maps of the Sala del Guardaroba illustrate the geographic understanding of the sixteenth century, highlighting both its certainties and gaps.

They show accurate representations of European and Mediterranean regions, reflecting established cartographic traditions and relatively reliable measurements. However, depictions of more distant lands are often imprecise.

Toponyms, trade cities, and political emblems

Africa’s coasts show recognisable outlines, but the interiors reveal areas still little known. Representations of the Americas display contours in the process of being defined, alternating indigenous names and European denominations, while Asia combines information from Arabic and classical sources with data derived from modern accounts.

Of particular interest are variable toponyms, the placement of imperial cities along maritime routes, discrepancies between reliefs and rivers compared to contemporary standards, and the use of cartouches and coats of arms that create a politically charged geography. These details reflect the mentality of the time.

A state-directed encyclopedic collection

Naturalistic objects, mineral samples, and botanical and zoological curiosities positioned the hall within European networks of encyclopedic collections.

Astronomical observations, the use of meridians and parallels, cartographic projections, and the construction of globes acted as devices of truth and persuasion. Through these methods, power was grounded in rationality and calculation.

A central and prominent presence

The central element of the hall was the large terrestrial globe, conceived as a complement to the wall maps. It allowed the world to be visualised in three-dimensional form, offering a perspective different from planar maps.

Its sight gave the hall a theatrical character: the visitor could move around the sphere, compare its representations with those on the doors, and perceive the totality of the world as a coherent and finite whole.

The theatricality was integral to Medici political communication, which sought to astonish and convince through spectacularity and compositional order.

Historical testimony of evolving geography

Today, the maps of the Sala del Guardaroba are precious historical documents. They show the geography of the sixteenth century, with its facts and uncertainties, and bear witness to the transition between medieval and modern wisdom.

Europe’s greater precision and maritime networks

Still, Europe reveals a great accuracy: its political and urban framework is rendered with care, and the underlying maritime routes are hinted at in the placement of emblems and ports.

What strikes most is the stratification of the rhythms of knowledge: the maps deliver a geography in progress, and precisely for this, they tell the story of how the world was imagined, measured, and ultimately represented.

For the Medici dynasty, the Sala del Guardaroba had a profound symbolic meaning. It represented Cosimo I’s power to collect, order, and dominate knowledge.

A political and cultural manifesto

The maps and drawers weren't just practical tools, but symbols of universal dominion. The hall communicated the idea that the family stood at the centre of the world, capable of understanding and governing it.

It was a political and cultural manifesto, a way to affirm the dynasty’s superiority through the representation of the globe. In an age when knowledge was power, the Sala del Guardaroba made this paradigm visible, integrating science, art, and politics into a single architecture of persuasion.

Incompleteness as a historical sign

Despite its ambition, the hall's project remained incomplete. Several maps were never made, and others turned out to be sketched. After Danti’s removal, the work was continued by Stefano Bonsignori, but didn't reach full completion.

The incompleteness is significant: it reveals the difficulties of an enterprise that sought to embrace the entire world, but collided with the limits of ability, time, and resources.

A Renaissance monument and its fragility

Thus, the hall remains a monument to Renaissance aspiration, but also to its fragility. It is an unfinished atlas, a theatre of knowledge that shows both the will to dominate and the awareness of the boundaries of the possible.

The absence of certain regions, the lacunous nature of some information, and the discontinuity of graphic rendering become eloquent signs of a modernity in the making, unafraid to display its partiality.

Atmosphere and spatial perception

Today, anyone entering the Sala del Guardaroba perceives a collected and intense atmosphere. The environment, not vast but enveloping, is defined by the large geographic maps covering the cabinet doors and by the central globe that still organises spatial perception.

Light and contemplative rhythm

The light, calibrated to protect and enhance the painted surfaces, suggests a slow rhythm of observation, favouring contemplation and comparison. The hall appears intimate, dense, intellectual: it invites one to linger, to read the cartouches, to trace coastlines and boundaries, to recognise the stratification of details.

The visitor senses Cosimo I’s intention to enclose the world in a practicable space, transforming geography into a language of governance.

The contemporary experience is twofold: aesthetic and critical. On the one hand, the beauty of materials, paintings, and the overall scenographic ensemble; on the other, the awareness of observing a political and scientific project that exposes its ambitions and its boundaries.

Universal knowledge and its constraints

The hall can be interpreted as a metaphor of the Renaissance. It embodies the aspiration to universal understanding, the confidence in humanity’s capacity to comprehend and order the world, and the will to transform knowledge into power.

At the same time, it shows the edges of this aspiration, the incompleteness that reveals the complexity of reality. It is a place that synthesises the tension between dream and fragility, order and chaos, familiarity and mystery.

Mental architecture of modernity

Its mental architecture, made of drawers, maps, globes, and allegories, returns the idea of a modernity born from the composition of disciplines, bodies of knowledge, and representations.

For this reason, the Sala del Guardaroba isn't just a room in the Palazzo Vecchio, but an emblem of Renaissance culture and its legacy: a room that becomes world, a world that becomes room, in which politics, science, and art hold together.

Archive and atlas, repository and theatre of knowledge

The area serves as a space where practical and symbolic functions come together, combining elements of an archive and an atlas, and where storage and the display of knowledge intersect.

Developed by extraordinary individuals of intellect, as a tool for governance and representation, and enhanced as living maps and the cosmic imagery of the ceiling, this space stands as a testament to the Renaissance ambition to catalogue and control the world.

The hall’s ensemble

The large maps on the cabinet doors constitute a visible inventory of global territories; the drawers recount a material geography composed of documents, diplomatic objects, natural models, and treasures; the central globe returns the sense of totality.

Today, in its intimate, dense, and intellectual atmosphere, it continues to speak, inviting reflection on how knowledge shapes architecture and how architecture influences the language of politics.

.avif)