Starlight sometimes behaves like a mischievous cartographer, sketching invisible highways across the night and daring us to pretend we can’t see them. It threads faint suggestions of order through the darkness, as if the cosmos were quietly inviting us to trace its secret geometry.

Even so, one of those imagined routes has shaped our understanding of the heavens more than any other, guiding not only how we map the sky but how we’ve told time, built myths, and imagined our place in the universe.

The ecliptic line is the apparent annual path of the Sun against the background of the stars. Although nothing physical marks it– no glowing trail, no cosmic seam, this bar governs the structure of the sky as humans have understood it for millennia. It’s the backbone of calendars, the reference for astrology, and the foundation of classical astronomy.

Along this lie the zodiac constellations, the seasonal turning points, and the rhythm that ancient observers used to anchor their rituals and agricultural cycles. The tilt of Earth’s axis, the changing length of days, and the shifting constellations of the night all play out in relation to this subtle, imaginary curve. In its quiet way, the ecliptic has become one of the most influential fictions humanity ever agreed upon– an invisible guide that continues to shape how we read the sky.

A Line That Isn’t There, Yet Shapes Everything

The Earth orbits the Sun on a plane, and because we observe the sky from Earth, the Sun seems to move along a circular route across the celestial sphere. This illusion is so consistent that ancient civilizations recognized it long before they understood the underlying means. They started to notice how the Sun always traveled through the same band of stars, consequently returning to the same points year after year. This band became what we know today as the zodiac.

The ecliptic is tilted about 23.5 degrees relative to Earth’s equator. That single angle, small enough to seem trivial on paper, is astonishingly responsible for the seasons, the changing height of the Sun in the sky, and the shifting length of days. Because Earth’s axis leans rather than standing upright, the Sun appears to wander north and south along this slanted path over the course of a year. That wandering changes how directly sunlight reaches different parts of the planet, redistributing warmth, reshaping weather patterns, and setting the cadence of growth and dormancy in the living world.

This inclination also determines the Sun’s daily arc, sometimes soaring high and lingering long, sometimes skimming low and slipping away early. Civilizations have built entire systems of meaning around these variations: solstices marking turning points, equinoxes balancing day and night, and countless cultural traditions tied to the Sun’s shifting behavior. Without the invisible line of the ecliptic, the rhythm of life on Earth would be unrecognizable, stripped of the seasonal contrasts that have shaped ecosystems, agriculture, and human imagination for thousands of years.

The Zodiac: Twelve Constellations on the Sun’s Road

An interesting aspect is that along this invisible line, twelve constellations arrange themselves into the zodiac. Constellations themselves are the 88 officially recognized patterns of stars that astronomers use to divide and map the sky. Classified by the IAU (International Astronomical Union), each one occupies a defined region of the celestial sphere and carries a name inspired by mythological figures, animals, or symbolic objects. Although their stars appear grouped together from our viewpoint on Earth, they are in reality separated by immense distances in three‑dimensional space, linked only by the perspective from which we observe them.

The twelve zodiac constellations are neither evenly spaced nor equal in size, yet the Sun appears to pass through each of them over the course of a year. This annual journey is what gives the zodiac its structure and its enduring significance, marking the Sun’s steady progression along the ecliptic and anchoring the cycle of seasons that has guided human life for millennia.

We usually think of zodiac signs as labels tied to our birthdays, determined by the day and month on the Western calendar. Yet what most of us never notice about our own sign is the astronomical story behind it.

Aries marks the spring equinox, the moment when the Sun crosses the celestial equator moving north. Taurus and Gemini follow as the Sun climbs into early summer. Cancer marks the Sun’s northernmost reach at the summer solstice. Leo and Virgo preside over the late summer sky. Libra hosts the autumn equinox, when the Sun crosses the equator heading south. Scorpio and Sagittarius lead the Sun toward the deepening cold of winter. Capricorn marks the winter solstice, the Sun’s southernmost point. Aquarius and Pisces then guide the Sun back toward spring, completing the cycle once more.

These constellations became symbols of time, agriculture, and mythology. Farmers used them to track the seasons, astronomers used them to map the heavens, and pagans used them as a sacred calendar– a living cycle that explained how the cosmos influenced earthly life.

The zodiac wasn’t merely a decorative ring of stars, but a practical tool for survival. When the Sun entered Taurus, it signaled the time for planting. When it reached Virgo, it marked the season of harvest. The sky became a calendar long before humans invented writing.

The zodiac is a direct reflection of the geometry of Earth’s orbit. The constellations, along the ecliptic line, are simply those that lie in the plane of Earth’s revolution around the Sun. Their significance arises from physics, even if ancient interpretations were mythological. What people saw as divine symbols were also the stars that happened to align with the Sun’s path. Yet this coincidence shaped entire civilizations. The zodiac became a universal language shared across centuries.

Over time, the zodiac evolved into a framework for storytelling. Each constellation became a character in a cosmic drama. Aries the ram, bold and energetic, honored the rebirth of spring. Leo the lion embodied the strength and heat of summer. Capricorn, half goat and half fish, symbolized the harshness and mystery of winter. These stories were helpful devices that allowed people to remember the sky’s patterns. Mythology became a vessel for astronomy, and astronomy gave structure to mythology.

The Celestial Sphere – A Model for Understanding the Invisible

To visualize the ecliptic, ancient astronomers imagined the sky as a vast sphere surrounding Earth. This celestial sphere became the primary tool for mapping the heavens. Here, the ecliptic is drawn as a great circle, intersecting the celestial equator at two points: the equinoxes. The celestial sphere allowed astronomers to track the Sun’s position throughout the year, predict solstices and equinoxes, understand the motion of the Moon and planets, create accurate calendars, and design instruments like astrolabes and armillary spheres.

Even today, astronomers still use the celestial sphere as a conceptual framework. Modern coordinate systems (right ascension and declination) are built on the same geometry. The celestial sphere simplifies the sky by projecting everything onto a single surface. Instead of dealing with the true distances of stars, which vary enormously, astronomers treat them as if they lie on a single shell. This concept makes it possible to measure angles, track cycles, and predict celestial events with remarkable precision.

The celestial sphere also shaped humanity’s understanding of the universe. For centuries, people believed the stars were literally fixed to a crystalline shell. Even after the heliocentric model replaced the Earth-centered cosmos, the sphere remained a useful mental tool. It still appears in textbooks, planetariums, and star charts. The ecliptic, drawn across its surface, remains the backbone of celestial geometry.

Over time, the invisible line and the constellations captivated the imagination of globe makers, inspiring them to craft celestial globes– beautiful objects that blended scientific precision with artistic expression.

These were three-dimensional representations of the sky, with constellations drawn on the surface and the ecliptic marked as a prominent circle. They were essential tools for navigation, education, and scientific study from antiquity through the Renaissance. A celestial globe typically includes the ecliptic, often highlighted or engraved, the zodiac constellations arranged along the line, the celestial equator forming a second great circle, major stars and mythological figures, and sometimes the paths of planets.

These globes were works of art. Renaissance globes, for example, combined astronomical precision with elaborate illustrations of mythological creatures. They embodied the union of science and imagination. Scholars used them to teach the structure of the heavens, sailors used them to understand the sky at sea, and artists used them as symbols of knowledge and exploration.

The ecliptic on a celestial globe is the organizing principle of the entire model. Without it, the positions of the Sun, Moon, and planets would be impossible to represent accurately. The globe becomes a miniature universe, and the ecliptic becomes its spine. By rotating the sphere, one can watch the zodiac rise and set, see how the Sun moves through the seasons, and understand why the length of days changes. In an age before digital simulations, a globe was the closest thing to holding the cosmos in one’s hands.

The Ecliptic and the Dance of the Moon and Planets

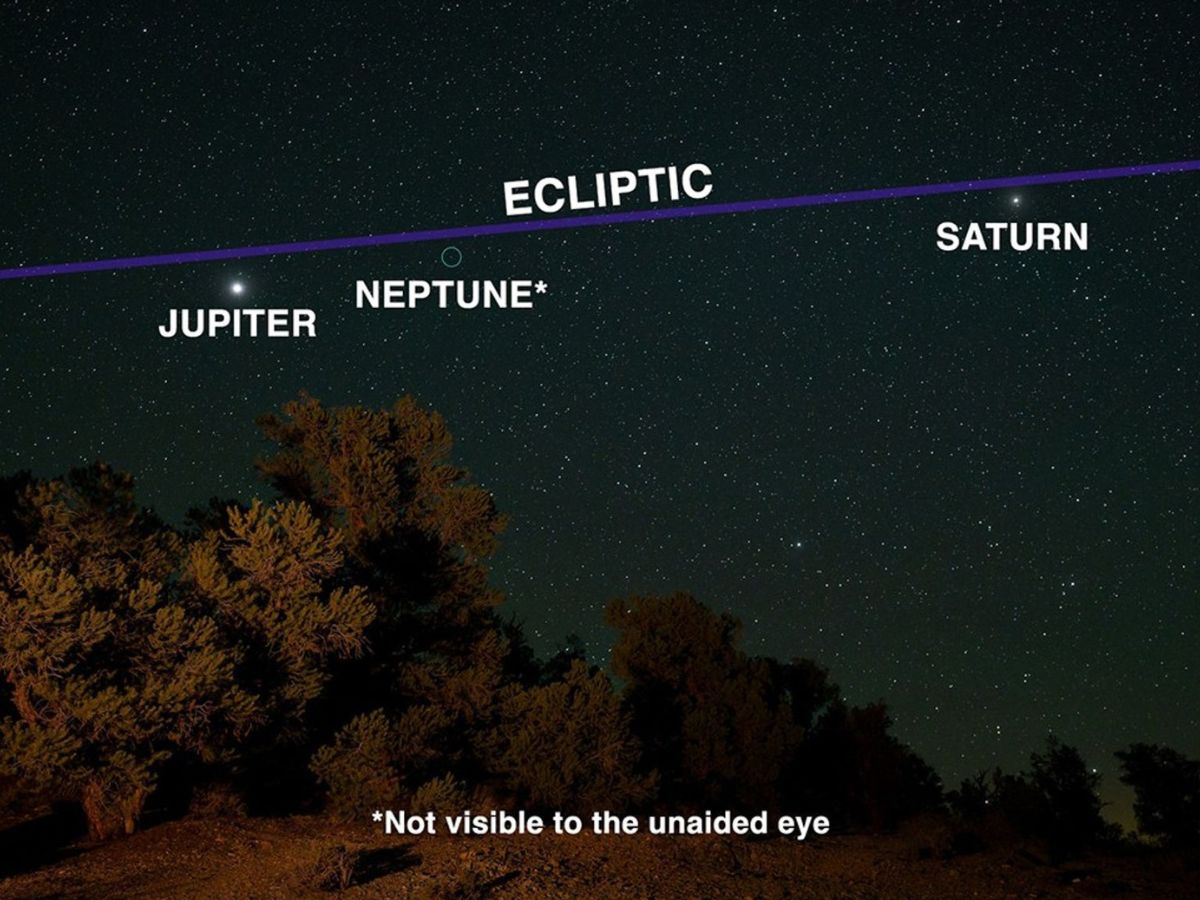

The Moon and planets also follow paths close to the invisible line. This is because the entire solar system formed from a rotating disk of gas and dust, leaving all major bodies orbiting in roughly the same plane. This alignment explains several key phenomena. Eclipses occur only when the Moon crosses the ecliptic at the right moment; planetary motion appears as wandering along the zodiac; retrograde motion (when planets seem to move backward) is visible only along this band.

The ecliptic is therefore not just the Sun’s path, but the shared stage on which the solar system performs its celestial choreography. The Moon’s orbit is tilted slightly relative to the ecliptic, which is why eclipses can’t occur every month. Only when the Sun, Moon, and Earth align at one of the Moon’s nodes (the points where its orbit intersects the ecliptic) can an eclipse occur. Ancient astronomers discovered this long before they understood gravity. They recognized that eclipses followed cycles, and those cycles were tied to the ecliptic.

The planets reveal their secrets only when viewed against the ecliptic. Their apparent wandering puzzled early observers. Why did Mars sometimes slow down, stop, and move backward? Why did Venus never stray far from the Sun? The answer lies in orbital geometry. Retrograde motion is an illusion created by Earth’s movement relative to other planets. But the fantasy is only visible because all planets stay close to the ecliptic. Without this shared plane, the sky would appear chaotic.

Why the Invisible Line Still Matters

Even in the age of space telescopes and digital star maps, the ecliptic remains fundamental. Astronomers use it to orient spacecraft and telescopes. Astrophotographers use it to predict where planets will appear. Calendar systems still rely on equinoxes and solstices defined by the ecliptic. Planetariums and celestial globes continue to teach its importance.

The invisible line is a reminder that Earth is part of a larger cosmic structure. It connects our daily experience with the sunrise, the seasons, and the length of the day to the vast mechanics of the solar system. The ecliptic line also plays a role in modern space exploration. Spacecraft traveling to other planets must follow trajectories that align with the orbital plane of the solar system. Mission planners calculate launch windows based on the positions of planets along the ecliptic. Even satellites orbiting Earth are influenced by the geometry of the ecliptic when engineers design their paths.

In astronomy education, the ecliptic remains a foundational concept. Students learn to identify it in the sky by watching the Moon and planets, and amateur astronomers use it to plan observations. Even casual stargazers notice that bright planets always appear along the same arc. The ecliptic is not a relic of ancient astronomy, but it’s a living tool.

The ecliptic is an invisible line, yet it shapes the visible world. It’s a string drawn in the motion of Earth itself. Through it, modern astronomers map the heavens and understand our place in the solar system.

It’s the line that carries the Sun, the zodiac, the planets, and the rhythm of the seasons. It’s the spine of celestial globes and the foundation of astronomical thought. The invisible line is, in truth, one of the most important lines ever imagined– a bridge between Earth and sky, between human culture and cosmic order.

.avif)